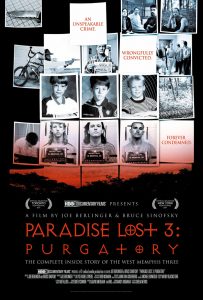

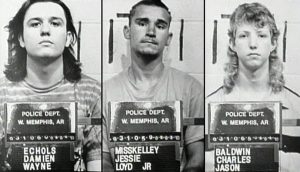

Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley, the teens notoriously known as the “West Memphis 3,” were convicted of brutally murdering three 8 year-old boys living in their hometown of West Memphis, Arkansas in 1994. Echols, only 18 years old at the time of the murder, was sentenced to death; Baldwin, who was 16, was sentenced to life in prison; Miskelley, who was 17, was sentenced to life in prison plus 40 years. But what sets these convicts apart is the belief and irrefutable evidence that they are innocent. The documentary chronicles the disputed trials and imprisonment of the West Memphis 3 and advocates the belief and near-fact that they did not commit the murders that have paused their life for 18 years. The movie’s release was delayed two months when the Arkansas Supreme Court released the trio from prison unexpectedly on August 19th, 2011, shortly before the film was to premiere. The directors, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, recount the lives of the WM3 (West Memphis 3) since the murder accusations up until their release, in a manner that the men deserve after their 18-year trial.

Aspects of the story are portrayed in “Purgatory” in a way that brings out one’s strongest feelings of contempt for the court of Arkansas, for the way that they handled such a serious crime. The film hints at Echols being wrongly targeted as a suspect because of his strange appearance and different personality. Baldwin was simply close friends with Echols and was dragged in by acquaintance, and perhaps by former charges of shoplifting and vandalism committed with Echols by his side. Officer Steve Jones, one of the police officers involved in the investigation, felt Echols was capable of murder, simply because drawings were found made by Echols of satan and other devilish symbols, and the murder scene was thought to be one of his satanic rituals. The three victims were hogtied naked and thrown in a creek and one of the boys, Stevie Branch, had his genitals removed. Quickly, and without real evidence, the police targeted the WM3 as suspects. This amount of ignorance and quick assumption from the investigators involved genuinely frustrates viewers. Real, heart-wrenching, and gruesome pictures and video of the crime scene are shown as well. The very sight of it disgusts the viewer, and makes one wonder how the police investigators could have jumped so quickly to conclusions, and more importantly: why was it allowed?

The documentary is able to draw out feelings of anger for the wronged by holding the viewer’s attention sternly. Where the film really begins to pick the brain is when interviews with Terry Hobbs, stepfather of 8-year-old Branch, are examined. The interviews are extraordinary, and the editors have skillfully edited them so that suspicion of Hobbs being the murderer slowly builds. Hobbs cannot pinpoint his whereabouts on May 5th, 1993, as seen in real interviews featured in the documentary. There was also a hair on one of the shoelaces around the boys limbs that was, years later, DNA tested and found to be Hobbs’s hair. Yet the cops had not even considered him as a person of interest, let alone a suspect for the crime, despite the facts thrown in their face–another terribly frustrating bit of information for the viewer. Meanwhile the innocent WM3 rot in prison for a crime they did not commit. Even John Byers, stepfather of Christopher Byers (one of the victims), feels strongly that the West Memphis 3 are innocent, and Terry Hobbs is blatantly guilty. The documentary features a clip of Byers holding a poster board, that states in its simplest form, reasons why Hobbs may be innocent and reasons why he would be guilty in a compare-and-contrast fashion. The guilty side dramatically outweighs the innocent side–one of the various points in the film helping the viewer develop more confidence and passion in the WM3 and their innocence.

A strong point in the documentary would be the amount of raw footage and real interviews and recordings with the WM3 and several others involved. Featured are interviews with the judge of the trials, the WM3, the parents of the victims, police investigators, and many more. There is also video footage of the crime scene, and recordings of Jessie Misskelley’s confession of the crime to the police. They had questioned Misskelley, whom is also borderline mentally challenged, for 12 hours straight, yet only about 45 minutes were recorded, and led him to confession through manipulation and fatigue. Misskelley states he would nearly just repeat what the police wanted him to say. Interviews with the convicted trio help form a connection and a passion for what they stand for. In one particularly interesting interview, Echols, whom was at the time sentenced to death and had been in prison for over a decade, states that he has “a rather amazing life.” The viewer develops a sense of respect for the calmness the suspects maintained throughout their lives despite one of the most frustrating occurrences to happen to a person, and that is an understatement.

Many times a crime investigation can be intricate and a documentary may lose the viewer’s attention due to lack of understanding. Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory gives a detailed overview of the complicated case that is understandable to the common person. The Oscar nominated film gives the reader a lasting respect for the men convicted, left with a need for closure and further pursuance of the true murderer. It offers the idea that a court system may not always be right. It features real life footage and no dramatizations. The directors, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, captured the trials from the beginning when the now middle-aged men were just kids, and the last of the “Paradise Lost” series has been able to expose the truth that the WM3 needed and celebrates the freedom that they gained at last.