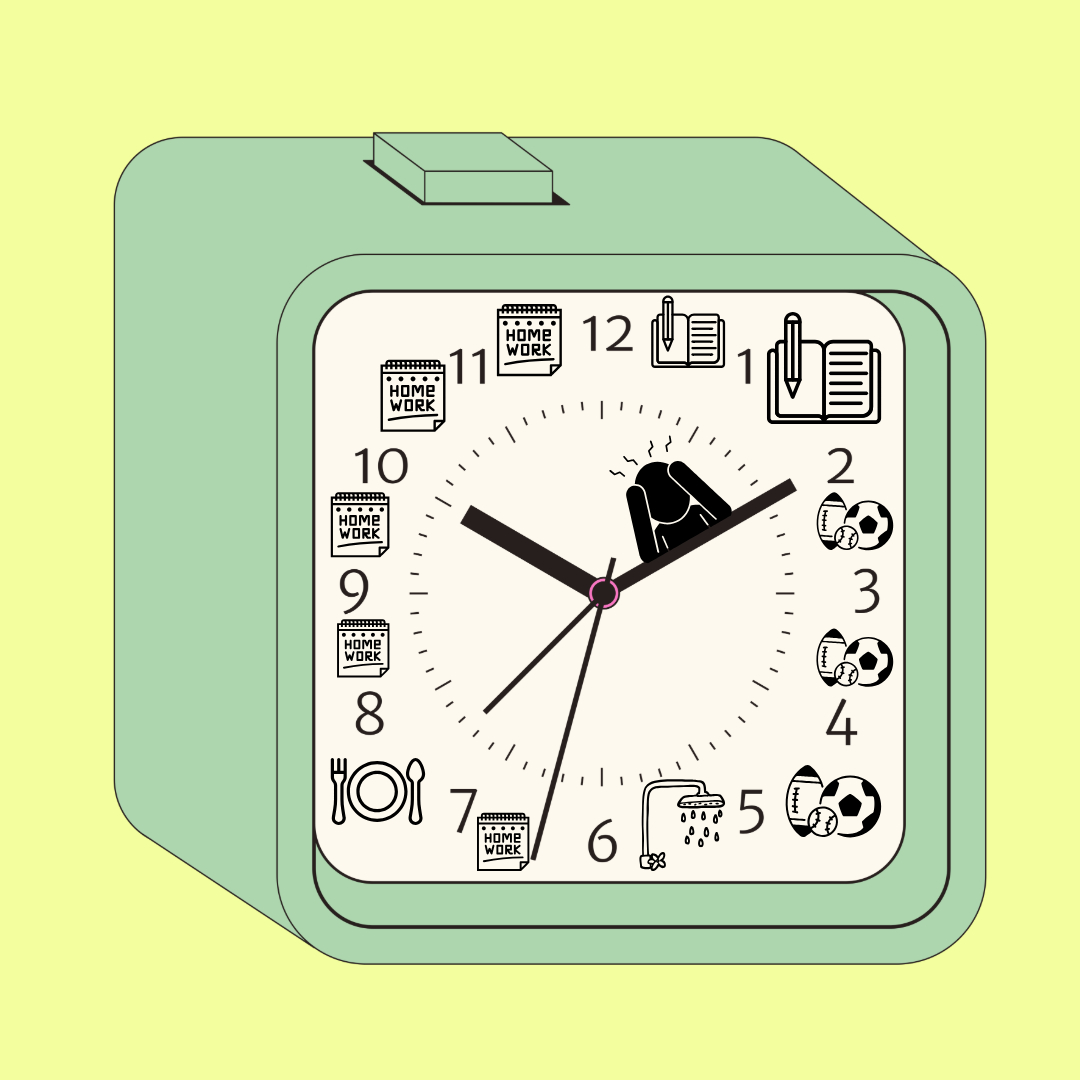

In many classes—particularly history and English classes—teachers decide to have graded discussions or debates, where students’ scores generally reflect the number of times they speak throughout the conversation. Although these discourses can be an effective way to talk about prevalent issues, the manner in which they are run needs to be reevaluated.

There is no doubt that discussions can be an effective way of learning; students may have a civilized and productive debate on a certain topic and have the ability to share their ideas freely. They also encourage students to think independently and on a deeper scale, as most seminars are primarily student-run as opposed to the teacher being involved. Additionally, Socratic seminars combine multiple different areas of comprehension, such as reading, listening and critical thinking; thus, for the students who enjoy participating, this can be a good learning opportunity.

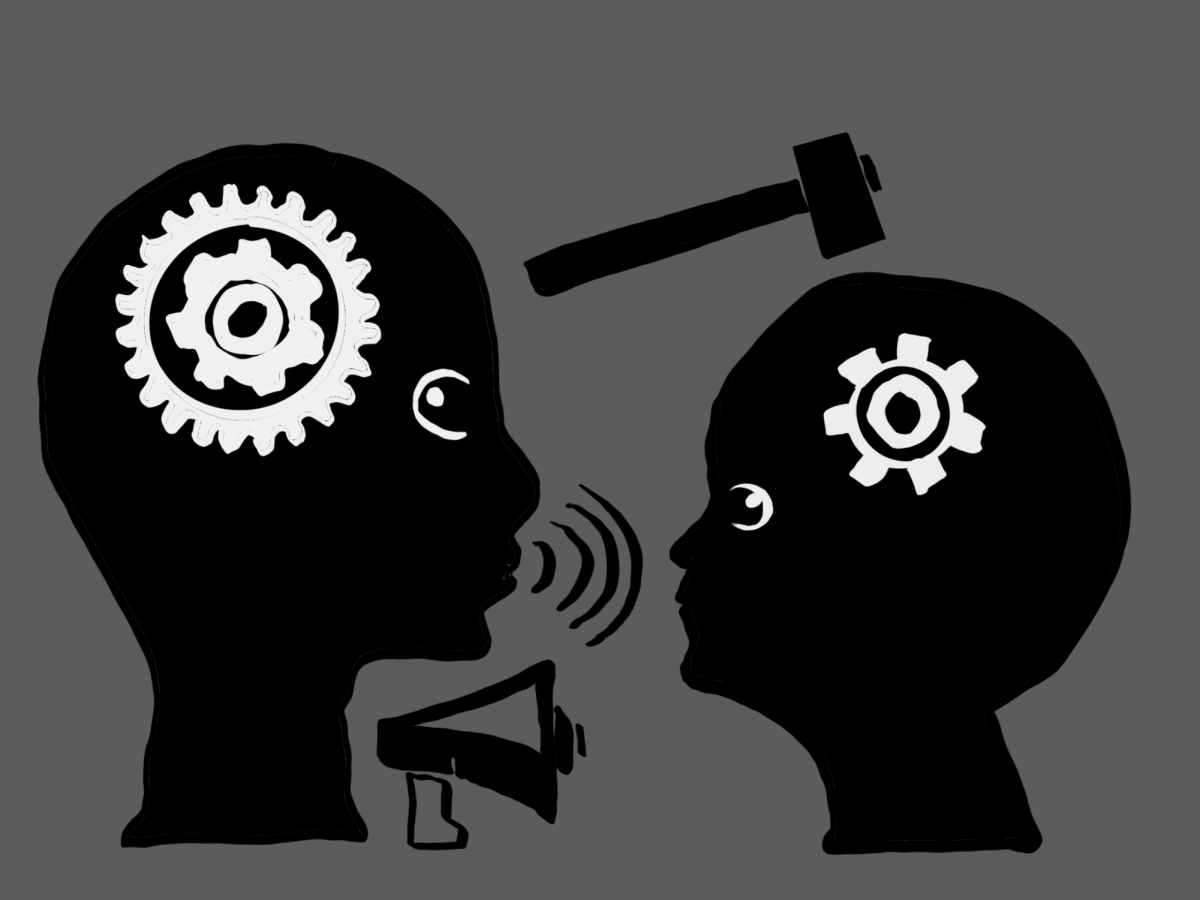

During a typical in-class discussion, there are usually three types of students: those who share their opinion once or twice, those who opt not to say anything and those who dominate the conversation. This mix of people does not make for a quality discussion, as some students are more focused on the amount of times they speak rather than the quality of what they are saying.

One could conclude that the student who says the most things has the best ideas; however, often times the person that does not speak has strong points, but the student who speaks more frequently is simply talking to improve his or her grade, which proves that Socratic seminars are not always an accurate measure of ability. Also, even when a person does have good ideas, sometimes they are not able to bring them up because certain people are taking over the conversation and not allowing them to voice their opinion.

If a student does not feel comfortable sharing their thoughts during the discussion, there are usually two different options: they get a poor grade or they have the opportunity to do an alternative assignment for the teacher to measure the student’s comprehension on the topic. The latter is a much more effective way to provide quieter students the chance to share their thoughts without the fear of being judged, not knowing what to say on the spot or speaking in front of the entire class. Students can either do a separate assignment, or they can turn in written answers to the questions passed out prior to the discussion.

However, by giving students a zero or a low grade for not saying anything, the message teachers are implying is that the students who talk the most are superior to those who may have good ideas but just do not feel comfortable sharing them. Without a doubt, students who provide quality insight into the topic at hand should receive a high grade; on the other hand, students who speak several times but simply discuss surface-level content, such as “I agree with this person because…”, should not be graded the same as the aforementioned student.

Different students have different learning styles; some sort out their thoughts best when they are directly in the conversation, and others learn best when they listen to others. Students with the second type of learning style should not be punished for being the way they are; rather, they should be given the option of whether or not they want to join the discussion.

Another factor that contributes to the lack of a meaningful discussion is the environment that students are in: classes where students are more comfortable with each other are more likely to be engaged than those where students rarely interact. Teachers need to facilitate a learning environment in which students are allowed to participate in a way that makes them feel secure. For instance, if teachers have students regularly work in randomly assigned, smaller groups, they will be more apt to participate in discussions because they are used to talking to and working with those students. In contrast, if students never interact with each other in more personal circumstances, they are less likely to volunteer. Few people would want to share their political views with someone that they have never even had a conversation with before, so communication on a smaller scale is key.

The issue at hand is not with having Socratic seminars or debates—they can be a great way to engage students; the problem is that students should not feel pressured to speak if they do not want to. The truth of the matter is that some people are not comfortable speaking in front of the class, and there is nothing wrong with that; instead, teachers should adjust the way these conversations are run so that they accommodate all types of learning styles. This may mean choosing not to grade the discussion, offering an alternative assignment or holding multiple, smaller discussions as opposed to one large one. Overall, balance is an important factor to make in-class discussions meaningful, but forcing students to participate when they do not feel comfortable doing so is a flaw that needs to be changed.