Walpole’s Alcohol Education Programs Need Reform

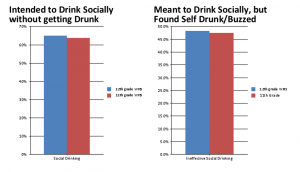

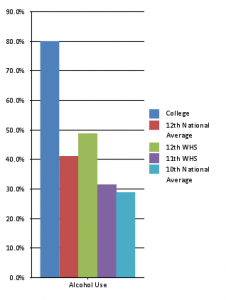

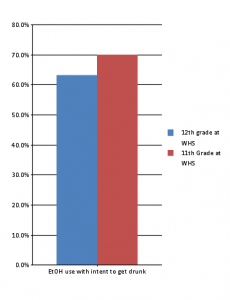

The unsigned editorial below was approved by the Rebellion Editorial Board and was published in the April publication. Since that publication, Bridge Program Coordinator Keith Wick shared the attached graphs from his presentation on the “Harm Reduction Model” which he presented to the Walpole Alcohol and Drug Coalition. His graphs are based on a survey he distributed to the entire Junior Class and Senior Class in November of 2014. The Rebellion decided to share these graphics to further inform the public. The article, however, has not been changed.

A North Andover mother appeared in court to face charges after hosting a party with underage drinking at her home on Tuesday, March 31. Over 50 guests — including her children — attended the party, where the mother allegedly charged an admission fee of $5 per person. She was charged with delinquency of a minor, procuring alcohol for a person under 21, and keeping a disorderly house; additionally, she is required to stay alcohol free and to have no contact with any minors other than her children.

While her situation is an extreme (most likely because she charged for entry), her negligence is only abnormal because of her explicit awareness of what most teenagers actually do. According to Walpole’s results from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 2011 — an anonymous survey given to random public high schools every other year — 23.4% of Walpole teenagers have tried alcohol by the age of 13. Some parents are not aware of this behavior; however, many parents are knowingly ignorant.

Underage drinking is a huge problem in America — in 2013, the Institute for Social Research reported that roughly 68% of high school students have engaged in underage drinking at least once. In Walpole, the majority of youth alcohol education comes from school mandated health classes starting in middle school. Students learn the effects of alcohol on the body and the legal consequences of participating in underage drinking. Additionally, the Walpole Coalition for Drug and Alcohol Awareness hosts annual video and poster contests to raise awareness in teenagers about drug and alcohol use, what those may lead to, screening of rehab centers, etc. However, the focus of both of these programs is why one should not drink and how one can refuse a drink. So what happens when a student does choose to drink? Without any information on responsible drinking readily available to teenagers, how can we expect teenagers to make smart decisions about alcohol?

Underage drinking is a dangerous issue in our society, but what is even more dangerous is teenagers engaging in underage drinking without any knowledge or resources about how to drink responsibly. So rather than preaching an abstinence only approach towards the underage consumption of alcohol, adults instead need to educate teenagers honestly and realistically about not only the consequences of drinking, but also about how to drink responsibly and safely in the event that a teenager does choose to drink.

The first step towards a safer and more effective method of alcohol education is removing myths and stigmas about alcohol. We as a society need to realize that alcohol is not simply a poisonous toxin—it is also not an idealistic remedy for social pressures. When educating teenagers, adults tend to utilize scare tactics and horror stories in order to discourage teenagers from drinking. And although educators try to paint alcohol as a dangerous substance, our culture glorifies the consumption of alcohol. Between beer commercials featuring women in bikinis and men with six packs and popular artists singing about parties and drinking, minors are frequently exposed to the idea that if one drinks alcohol, they will achieve social idealism. In reality, neither side is correct.

Instead, adults should educate teenagers about what alcohol really is – a normal part of adult culture that has consequences when abused. Responsibility for alcohol education should not be left to schools; instead, parents should honestly educate their children about the dangers of alcohol early on in order to not only teach them why underage drinking is wrong, but also to normalize the idea of alcohol consumption. Parents need to understand that many teenagers will and do drink, and teenagers are far more likely to be honest about their drinking habits if their parents do not overreact about the issue of underage drinking.

Of course, this is a feat easier said than done, as underage drinking does have serious legal consequences and parents are right to want to keep their kids safe. However, the repercussions for irresponsible drinking are even more dangerous; for example, according to the Administrative Office of the Courts, over one million teenagers drove while drunk in 2011, and 8 teenagers die every day from drunk driving. If one has an honest conversation with his or her parents about alcohol, he or she will likely be more comfortable asking for help such as a ride home, which reduces the possibility of drunk driving. The discomfort of asking a parent for guidance is worth the potentially fatal effects of underage drinking. But before teenagers can open up to their parents about drinking, our society needs to change the way we think about and treat alcohol, particularly involving underage drinkers, so that teenagers can safely have these conversations and ask for help when needed.

Because of the stigma surrounding alcohol, teenagers who make the decision to drink often have little to no information on how to drink responsibly. Teeangers need to know about things sch as alcohol equivalency so that they understand that a sip of beer is far different than a sip of vodka.

Rather than strictly limit any alcohol consumption until one is an adult, European countries often do not have a drinking age; instead, they introduce alcohol to minors gradually so that they can learn to be responsible when they reach the legal purchase age (which is usually 18). The American cultural stigma of alcohol is completely removed from European society, which allows European teenagers to learn how to drink alcohol safely under the guidance of adults.

The alcohol epidemic is not an issue that legal reform will change; instead, our society and our respective alcohol education programs need to take a different perspective in order to see a change in teenage drinking habits. Underage drinking is an issue that will not fix itself, and it is up to our culture to remove the stigma, provide more information, and hopefully teach teenagers to be safe and responsible whether or not they drink.