By the Rebellion Editorial Board

For many high school students, the period of time between waking up and arriving in homeroom is one of the most stressful parts of one’s day. Between driving through the busy morning traffic, waiting in the extensive line of cars in front of the school, and struggling to maneuver through the crowded parking lot among other drivers and students who are equally as late, high school students face a number of challenges that could potentially hinder their timeliness to homeroom.

But for administrators, punctual daily attendance is an extremely important habit to develop for the future, and students should strive to arrive to homeroom on time every day. But although regulating students’ tardies is undoubtedly a necessary school policy, the unnecessarily strict guidelines of the current tardy policy encourages students to skip school altogether rather than to arrive to school late.

Up until this year, the school’s policy on tardiness was firm but reasonable — a student could be late to homeroom four times per semester or to first period six times per semester before the attendance office issued him or her a detention. This policy forced students to make a daily effort to be on time but was lenient enough to cover occasional tardies that were often out of students’ control. With this policy, administration issued 84 tardy-related detentions between September 1, 2013 and November 21, 2013.

But at the beginning of this year, administration enacted a new policy that greatly reduced the number of times a student could be tardy before he or she had to serve a detention. Students can arrive to homeroom late two times and do not have to sign in with the attendance office; however, on the student’s third offense, he or she has to serve a detention that same day. Additionally, students can only come in to school late after homeroom one time before he or she has to go to detention. The numbers reset at the end of every semester.

One of the best received aspects of the new policy is how students do not have to go to the attendance office in the morning if they are late to homeroom. In the past, students had to wait upwards of ten minutes in line before they could continue to class; as a result, many students who were only a few minutes late to homeroom ended up missing the beginning of their first period class.

But as a result of this policy change, many students opt to skip school for the entire day in order to avoid receiving a detention.

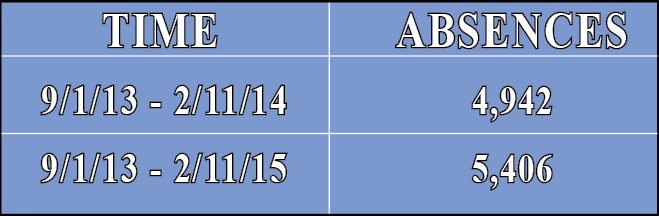

Compared to last year’s 4,942 total absences between September 1, 2013 up until February 11, 2014, the student body has had 5,406 total absences between September 1, 2014 and February 11, 2015. The 9.4% increase in absences is not a coincidence. Rather than promoting timeliness, the new policy encourages students to miss school completely rather than to come in to school late.

“I’d rather not go to school than go in late and get a detention,” said senior and Rebel Report anchor Brendan Jeannetti. “If I were to get to the parking lot and realized that I’m late, I would probably drive back home because I’d rather go home than get a detention for coming into school a minute late.”

Many students who would previously consider coming into school late due to oversleeping or illness now choose to skip school entirely instead of receiving a tardy because students have a more reasonable six unexcused absences per semester.

Senior Katie Smith — an AP student, NHS member, and swimming state champion — said, “In the past, if I didn’t feel well in the morning, but then felt well enough to go to school in the afternoon, I would consider going to school late. However, now that I’m going to be penalized with an hour for deciding to go to school, I prefer to stay home.” If students are a few minutes late, the punishment makes sense. But should students who come in to homeroom a few seconds late be punished the same as students who come in five or more minutes late? And should all of those students be punished the same as students who receive detention for behavior-related issues?

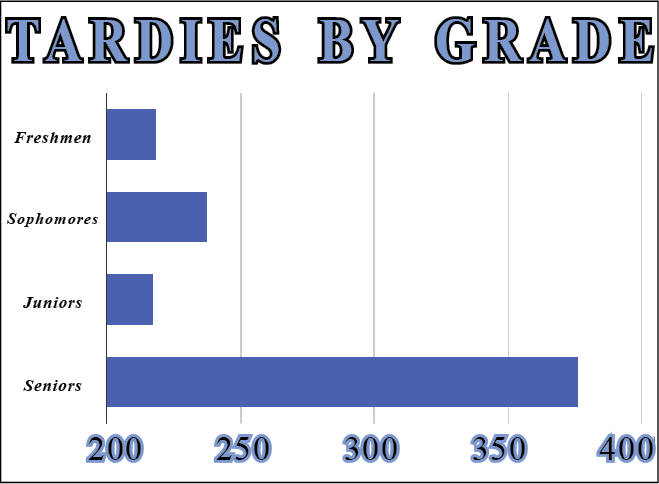

As a result of the new policy, the number of tardy-related detentions has increased to 166 as of November 21, 2014, which is almost twice the number of last year . Although students should have some sort of punishment due to a large number of tardies, detention is an unreasonable consequence based on the severity of the offense. Students with behavioral issues should not receive the same punishment as generally good students who arrive to school late.

“I have never ever gotten a detention in my four years at Walpole High,” said senior and NHS member Maureen Herlihy. “I feel that it is unfair that I got one for being less than a minute late for homeroom twice in the entire semester. It does not seem fair that being a minute late to homeroom translates into an hour of detention.”

The policy is also inconsistent from homeroom to homeroom depending on the leniency of the teacher. While some teachers do not penalize students so long as they are not more than a minute or so late to homerooms, others require that students are seated before the bell rings. Because of the disparity between teachers’ adherence to the policy, some students are held to a different standard than others and therefore are punished more severely for the same offense.

The changes to the high school tardy policy does little to improve students’ daily attendance or timeliness to school; rather, the new rule punishes students far too severely compared to the seriousness of the offense. Additionally, the policy promotes inconsistencies between homerooms due to teachers’ personal tardy policies. But perhaps most importantly, the policy prompts students to choose absence over tardiness, which inspires more students to skip school altogether in previous years. If a student is going to be late, he or she should not see skipping school as a more desirable option to coming in late.

The harsh change between last year’s policy and this year’s policy is not only unfair to students, but also encourages harmful habits that will affect students in college and in the working world. For the benefit of both students and teachers, administration should consider revising the new tardy guidelines in order to craft a new policy that is more fair and more reasonable than the current policy. Until administration creates a policy in the interest of the students, the new policy will continue to backfire on administration and spike students’ absences rather than instill good habits to improve students’ futures.